Bees Need a Thanksgiving Meal, Too

By Lauren Saurs

On one early December weekend, I walked out of Decipher Brewery and was struck by the vibrant golden hue of some remaining goldenrod amongst the clumps of snow that had fallen a few days prior. Now this sight is impressive on several fronts. First of all, props to this local business for having a pollinator bed right beside their front door! Second of all, goldenrod is an absolute champion of late fall perennials for providing beauty and most importantly food for pollinators such as bees. In this blog post, I will discuss some of the best late blooming flowers you can add to your yard to help provide food for bees late into the year, when little else is available.

I am going to date myself here and tell you I grew up in the early 90’s. Ever since I was a small child, I have been hearing about the decline of bees. It has been a fact of my entire existence that bee populations have steadily decreased due to habitat loss, climate change, and widespread diseases. I hate to say it, but I hear those three factors in conjunction with a lottttt of scary things these days, and it all starts to become a steady hum of background noise. Well, in case you also find yourself losing the plot from time to time, I am here to help bring it into focus.

Humans evolved in a pollinated world. That means we rely on bees and other pollinators in order to provide a complete healthy diet necessary for our development. Most of our carbohydrates come from wind pollinated plants like wheat and rice. However, most of our micronutrients come from fruits, vegetables, and nuts. Bees are crucial for the pollination of foods such as apples, watermelons, tomatoes, cucumbers, most berries, coffee, I repeat, coffee, almonds, cashew nuts, and much more. These pollinated foods are providing most of our vitamin A, C, E, and folate along with dietary minerals such as potassium, iron, fluoride, and calcium. Conservation of bees is thus fundamental for continued food security and should really be at the forefront of everyone’s minds. How absolutely cool is it that you can make a difference and help uphold our food web for everyone by planting more flowers!?

A bee contributing to our coffee habits.

If that didn’t capture your attention, let me tell you some quick fascinating things about bees. Humans evolved around 300,000 years ago. Bees evolved in the mid-Cretaceous, or 70 million years ago. Throughout our history, we’ve had close relationships with bees. In fact, the oldest evidence of beekeeping is found in the solar temple of the Egyptian pharaoh Newoserre Any. This was during the Fifth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, 2494–2345 BCE.

The Quest for the Perfect Hive: Relief from the Solar Temple of Nyuserra, Fifth Dynasty

Researchers are shocked that their depiction of beekeeping is as advanced as any modern day beekeeping practice. Separate from the Old World, beekeeping also developed in Mesoamerica. There is archeological evidence from the Maya Late-Preclassic period, 300-250 BCE, of beehives such as hollow logs or cylindrical ceramic vessels that were used by the people of that time. The ancient Mayan city of Tulum, Mexico, is watched over by the Descending God, Ah-Muzen-Cab, the god of bees and honey.

Ah-Muzen-Cab, god of bees and honey.

The older I become, the more I just want the bees in my yard to be happy. Could it be that this simple desire has its roots in ancient relationships between humans and bees?

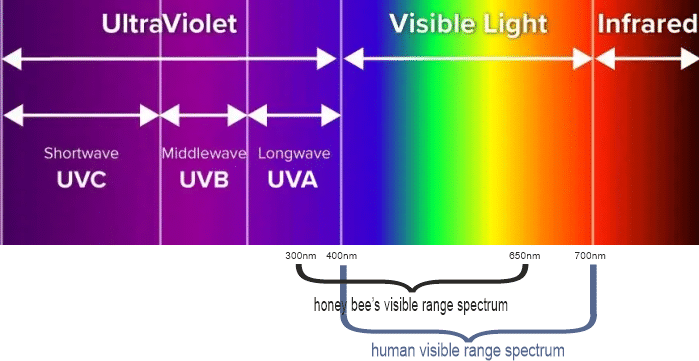

Out of all the threats affecting pollinators, landscape change is the most important factor. That means that the biggest difference we can make is to plant more! The best things you can add to your gardens are diverse, flowering plants at varying heights, and majority native species. In an earlier AG blog post, we discussed early blooms for bees. In this one, we will specifically take a look at blooms lasting late into the fall. All colors of flowers are welcome, but did you know that bees see into the ultraviolet range? That means they have a hard time seeing red and tend to show a preference for blue and purple flowers.

What a flower might look like to a bee.

Annuals are acceptable food sources, but in general they support a narrower community of pollinators because they tend to be very short and they are often double flowered which have little to no nectar that bees can access (think mums unfortunately).

Here is a list of bee approved fall blooming snacks with their bloom color and times. The natives to the Piedmont region are starred.

Symphyotrichum (Asters)*: “Of all the native wildflowers in the Piedmont, Asters may be the best food source for migrating and overwintering Monarch butterflies, European honey bees, native bees, bumblebees, and other pollinators” (Piedmont Native Plants 2nd Edition, 28) white, pale blue, purple, violet; late summer-October; many different types to choose from

Bee feeding on an aster bloom.

Asclepias tuberosa (Butterfly weed)*: Neon orange, yellow, red bloom; May-August

Asclepias incarnata var. pulchra (Swamp Milkweed)*: pink, ruby; July-September

Vernonia noveboracensis (New York Ironweed)*: magenta to raspberry; July-September

Pycnanthemum (Mountain Mints)*: “they consistently attract the greatest number and diversity of insect pollinators in the Piedmont region” (Piedmont Native Plants 2nd Edition, 20). White blooms with magenta speckles; June-August

Bee on Pycnanthemum muticum (Mountain Mint)

Eupatorieae tribe (Boneset, Joe Pye, Mistflower, and Thoroughwort)*: white, pink, lavender, blue; July-October

Bees on Joe Pye Weed.

Lobelia cardinalis (Cardinal Flower)*: red; July-October

Lobelia siphilitica (Great Blue Lobelia, Blue Cardinal Flower)*: lavender, blue; August-October

Liatris pilosa (Blazing Star, Grassleaf Gayfeather)*: lavender; August-November

Solidago (Goldenrod)*: pale to bright yellow; August-October (this is a rockstar pollinator plant and there are many species to choose from if you don’t like the look of one!) (There are also shade tolerant varieties!)

Passiflora incarnata (Purple Passionflower or Maypop)*: blue, purple white; May-August

Feasting upon a passion flower.

Clematis Virginian (Virgin’s Bower)*: white, cream; July-September (not to be confused with the invasive, Sweet Autumn Clematis, which is nearly identical)

Agastache “Blue Fortune”: soft blue, purple; July-October

Japanese Anemone: white, pink, purple; August-October

Calamintha: white to pale blue; June-first frost

Dahlias (with an open center): any color; July-first frost

Not all dahlias have accessible pollen centers! Look for varieties that are more simple with open, yellow centers.

Nepeta: lavender, blue; late spring-late fall

Salvia: what list would be complete without salvia!? A pollinator favorite that often lasts through to the first frost, there are many varieties to choose from: some native, some perennial, some tender perennial, all colors.

I hope this blog post helps inspire you to add more flowers and diversity to your yard, community garden, or even porch containers! Nothing in nature exists in a vacuum. With these plants you are not just helping bees, but countless other insects, critters, and as we just read, humans. So the next time someone gives you a hard time about buying too many plants, you can tell them you are doing your part to save the global food supply.

-By Lauren Saurs